Category: Dominicana

Forgetfulness

“Josh and the Big Wall!” was one of my favorite episodes of VeggieTales. I was always frustrated with the beginning, however, when Bob the Tomato explained that the Israelites would have already gotten into the Promised Land if only they had listened to God.

When I was first learning these Biblical stories as a kid I fell in love with God, easily convinced of his love by his mighty wonders. Thus, it made no sense to me that they would disobey God, especially so soon after he had saved them from the Egyptians. “If I had been there,” I thought to myself, “If I had seen what they had seen, then I would have . . .” But the truth is, I myself was beginning to grumble in the desert.

Many years later, when I was a freshman in college, I felt called to pray but found that the Our Father was the only prayer I remembered; I just repeated it over and over again. What had happened to me?

I had forgotten God’s wonders of old. I had forgotten the Lord’s words of life. I had forgotten his goodness. I had forgotten the truth entrusted to the Church. I had forgotten all that the Lord had done for me. I found that I had turned away from my childhood faith. Forgetfulness is a tricky thing. It seems involuntary (at least it almost always seems so when we are the ones forgetting), but forgetfulness is certainly not blameless. It is an excuse, but never a satisfactory one. “Forgetting” to do my chores was never left unpunished.

And rightfully so. Forgetfulness is not spontaneous. It is gradual and secretive. I always found it easy to forget my chores when I turned myself away from my mother’s call upstairs and towards whatever game I was playing, show I was watching, or book I was reading. Certainly, Eve made it much easier to forget the divine command when she was thinking all about how “the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes . . .” (Gen 3:6). And the Israelites, turning to their perceived misfortunes, quickly forgot the Lord’s mighty deeds and that their “God is a God who saves” (Ps 68:21).

Sin makes us forget. Sin is a “turning away” that makes it easy to forget. And it has a compounding effect, as the only way we can justify our sin to ourselves is through a forgetfulness of God—such as forgetting his presence, his love, or that he is our final end. If we were able to forget that there is a God, then we would not be reminded of the eternal consequences of our actions and we would be able to live an easy life. Men “suppress the truth by their wickedness” (Rom 1:18). And with the truth suppressed, sin is easy.

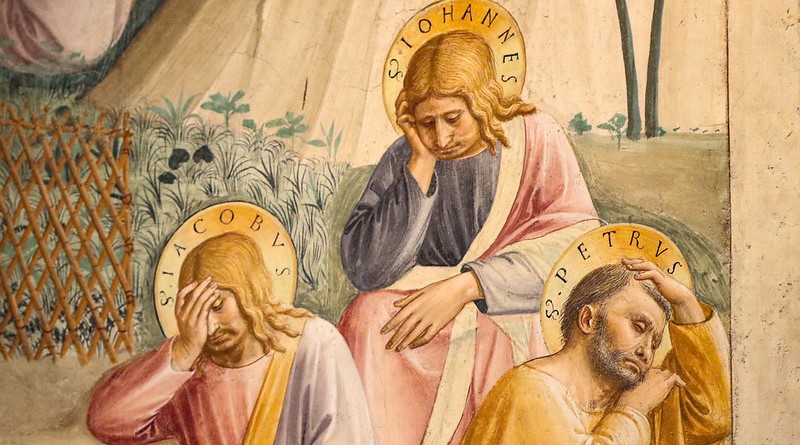

Thus, the awareness of God is essential: “there is no practice more vital to our spiritual growth; for the presence of God is indeed the very sunlight of the soul” (Anselm Moynihan, O.P., The Presence of God, 3). The saints teach us about this all-important awareness. Saint Peter is the perfect example: he sinks when he takes his eyes off Jesus (Matt 14:30). But then, after his denial, it is when the Lord “turned and looked at Peter” that Peter remembered (Luke 22:61). To be aware of God brings about the realization that he is steadily gazing upon us; that he is waiting, longing, desiring with great desire for the love only our hearts can give him. Cultivating awareness of God is nothing less than preparing for heaven. It is possible for man to forget anything if he allows his mind to go elsewhere. But you will find that it is always possible to remember again. “If you turn to him with all your heart and with all your soul . . . then he will turn to you and will not hide his face from you” (Tob 13:6).

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal on 8/1/2023.

Can You See That You Are a Prophet?

When we think of the Prophets, we think of Elijah and Elisha performing miracles, of the words and oracles of Isaiah or Jeremiah, and ultimately of Christ, who is the fulfillment of the Old Testament Prophets. The woman at the well says to Jesus, “Sir, I can see that you are a prophet” (John 4:19) because he had told the woman “everything” she had done, manifesting himself as “a prophet mighty in deed and word before God and people” (John 4:39, Luke 24:19). Given these prophetic words and acts of Jesus and the Old Testament prophets, we might balk at the idea that “the holy people of God shares also in Christ’s prophetic office” (LG 12). The Catechism goes further to say that by baptism, “the whole People of God . . . bears the responsibilities for mission and service that flow from [the prophetic office]” (CCC 783). You bear the responsibility for prophetic mission. You bear the responsibility for prophetic service.

“We wish to see a sign” (Matt 12:38). We might be tempted to think our participation in the prophetic office is watered down and insignificant, perceiving a gap between the biblical prophets and ourselves. We expect the prophet to predict the future or to produce mighty deeds; the biblical prophets have surely done this and none as excellently as Christ. A certain knowledge of God’s plan and miracles certainly follow from the prophets, but the prophet is not a simple fortune teller or magician. Two aspects stand out as more crucial to the prophet’s identity than oracles and wonders. And it is to these fuller aspects of the prophetic life that the Church calls you.

Firstly, the prophet is called to intimacy with God. Scripture says of Wisdom, “in every generation she passes into holy souls and makes them friends of God, and prophets” (Wis 7:27). True wisdom and true prophecy belong to the friends of God. The Lord himself calls Moses his “intimate friend” (Exod 33:17). All the prophets were friends with God, with Incarnate Wisdom himself showing us the fullness of intimacy with our Father. You too have received this call to intimacy: Wisdom comes to make friends, prophets, “in every generation.”

Secondly, the prophet must intercede for the people. For this, Moses is praised in the Psalms—he stood in the breach before God (Ps 106:23). God calls the prophets to be instruments of both justice and mercy. The prophets preach justice, but pray for mercy. God is desirous of this prayer and puts it on the prophet’s heart. Christ, again, shows us the might of intercessory prayer, perhaps most evidently in his prayer for the disciples (John 17).

The prophet is a friend of God and an intercessor. It is in this context that the Holy Spirit will give the gift of prophecy (1 Cor 14). Then the words and deeds we associate with the prophets will come to light. Saint Dominic’s intimacy with God and his prayer for sinners is the perfect model. By day he preached with firm truth and proved himself to be the joyful light of the Church, but all night he prayed alone before the Lord for sinners. Dominic stood in the breach before God, speaking “to God or about God,” as friend and intercessor.

This is what it means to bear the responsibility for prophetic mission and service: to become a friend of God and an intercessor for the people: “You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the greatest and the first commandment. The second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. The whole law and the prophets depend on these two commandments” (Matt 22:37-38). Our call to the prophetic office is not meant to be a pale imitation. You bear the responsibility for prophetic mission. You bear the responsibility for prophetic service. So what are you to do? Pray, pray.

✠

Photo by Sneha Cecil on Unsplash

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

The Cross, Again?

Why do we talk about the Cross outside of Lent? Hasn’t Jesus won the victory over death and sin already? Can’t we just sing our alleluias and eat Peeps? The Church continues to talk about the Cross, especially during the Easter season, to remind us that the Resurrection shows us the true meaning of the Cross. The Resurrection, rather than pushing the Cross into the shadows, illuminates the Cross and reveals it to be the greatest demonstration of God’s love for us. When we look at the Cross in the light of the Resurrection, we can see at least two things: first, God has power over death and sin; and second, God’s love is Cross-shaped.

When we look at the Cross in the light of the Resurrection, we see God’s incredible power over sin and death. One of the unfortunate consequences of familiarity with our Lord’s Passion and Death is that we can become desensitized to the depths of the suffering that Christ endured at the hands of the Romans. The beatings, the scourging, the crowning with thorns; being torn to shreds, stripped, nailed, and left to die on a piece of wood—all of this was deeply traumatic.

Jesus predicted his Passion again and again throughout his ministry because he knew that the scandal and darkness of the Cross would frighten his disciples and that they would be tempted to doubt him. It is only in the light of the Resurrection, in the light of God’s power, that the disciples are able to see the suffering and death of Christ, not with merely human eyes, but with eyes of faith. They are able to see the suffering and death of Christ, not as something to be ashamed of, but rather, something in which to boast. In the light of the Resurrection, the Cross becomes the power and the wisdom of God.

Again, in the light of the Resurrection, we see that God’s love is Cross-shaped. It is through the love of Christ that we know the depths and the heights of God’s love for us. The Resurrection reveals that Christ’s sufferings and death were filled with love for the Father and for us. Saint Paul reminds us of this in his Letter to the Romans: “But God shows his love for us in that while we were yet sinners Christ died for us” (Rom 5:8). It is precisely Christ’s death on the Cross for us sinners that reveals exactly how far God will go so that we might become His friends.

God goes to the Cross for us, taking our sins and our death with Him. The Resurrection shows us that it is in Jesus’ death that we have eternal life. What is true for Christ is true for us as well. In this Easter season, the Church invites us to look at our crosses in the light of the Resurrection. She invites us not to push our crosses into the shadows, but rather to expose them to the light of Christ’s Resurrected glory. Only when we see our crosses illuminated by this light will we be able to recognize the depths of God’s presence and love in the sufferings of our lives, and so look forward to the glories of the resurrection.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

The Tree of Prayer

One day at lunch, one of the priests with whom I live asked me a question I never expected near the end of my formation at the Dominican House of Studies: “Which tree are you most proud of?”

Now, it was reasonable that he did ask, seeing as I have planted about 50 trees around the House over the past four years. I planted most for shade, privacy, beauty, or fruit, so it took me a second to think which one I could say I was most “proud” of. But quickly I realized there was no real question about it. There was one tree that was not planted for any of these reasons, but simply because it was outgrowing its pot and needed to go somewhere.

This tree, when planted, was nothing more than a 6-foot-tall pole; it was just a skinny trunk with no branches or leaves. Had someone seen it, he would have thought it was just a stick that was stuck in the ground (as more than a few brothers had joked). Because of its less-than-remarkable qualities, this sad thing was placed out of the way near plenty of other trees, just in case it didn’t make it.

But I took a liking to this tree. Whenever I was praying my rosary in the backyard, I would stop in front of this tree and ask God to make this tree thrive.

This, in a way, can be seen as the story of a Christian at prayer. This tree was deemed the weakest of the trees that we planted that year, and in reality, it was. But the power of God is made perfect in our weakness (2 Cor 12:9). When we are at our weakest, we turn to God in prayer, prayer that is constant, prayer that is simple, and prayer that trusts even when it doesn’t see any results.

This tree was planted in the winter, many months before any signs of life could be expected. I would make my daily walk around the backyard, saying my rosary, stopping in front of the tree, then continuing on. Eventually spring came and I looked forward to seeing signs of life … but none came. All the other trees were coming to life. The sap was flowing. Buds, blossoms, leaves, and branches were all being brought forth. But from this weak little tree, nothing.

I continued my daily walks, almost giving up hope for the little guy, but still stopping in front of it, asking God to help it out. And surprisingly (though it should not have been) this is exactly what happened! First a small bud, and then a small branch; within months it was very clear that this small prayer had been answered.

I continued my prayers for it to thrive for a few years, but with a small addition: a short prayer of thanksgiving for the life that God had already bestowed upon this tree. This tree actually grew taller and more beautiful than any of the other stronger trees that we had planted in more ideal locations.

This small prayer that I offered up for this tree is the same prayer that I and many others have offered up for my life. We are called to be weak and meek by all worldly standards, but it is the meek that will inherit the world. Every Christian will go through winters in this life, when we are stripped of all that we thought made us beautiful, healthy, or alive. But “God does not see as a mortal, who sees the appearance. The Lord looks into the heart” (1 Sam 16:6-8).

By embracing a life of prayer that is continual, simple, and trusting, we become more alive than ever, even if we can’t always see it. Just as the tree loses its dead leaves, we are stripped of everything unnecessary. The life that was visible in the leaves for everyone to see retreats to the innermost parts of the tree where only God can see. This life may wait inside the Christian for days, months, or years, but it is always there, waiting to be brought forth at the right time, by the warmth of the rising Son.

✠

Photo (via Pixabay)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

Give It Up for God

What is the most important thing in your life? What would you do if God asked you to give it up? For some it might mean surrendering a talent: a beautiful voice or the world’s most accurate free-throw. For others it might be a loved one. For still others it might be their freedom. Imagine there’s no limit to the thing God asks of you—could you do it?

Mother Teresa, in her book Come Be My Light, writes of an experience that occurred at the beginning of a long period of darkness in her life. Expressing her dismay at how much God has asked from her, she writes:

“I just can’t express anything. I don’t know why [it] is like this—I want to tell, and yet I find no words to express my pain. Don’t let me deceive you. Leave me alone. God must be wanting this ‘aloneness’ from me. Pray for me. In spite of everything, I want to love God for what He takes. He has destroyed everything in me.”

Despite this darkness, by God’s grace, she continued giving up her life to God, little by little until there was nothing left. She surrendered quite literally everything. She even gave up her freedom, for after many years as superior general of the Missionaries of Charity, she asked Pope John Paul II to allow her to step down and let another sister run the congregation. He simply replied to her, “Do not refuse Jesus.” It was Jesus who asked her—through her congregation and then through the Pope—to give everything for the sake of his will.

Yet, this request of God is not just for the exceptional saint. It sometimes happens that even we ordinary people lose something important, even the one thing that defines who we are—that most important thing. Beethoven, one of the greatest composers ever, lost his sense of hearing. The French impressionist, Claude Monet, was blind for the last decade of his life. Even in our own Dominican family, Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, one of the brightest modern minds of classical Thomism, lost much of his ability to think before he died.

The reality is that even after you’ve given everything, there is still one thing that God desires. He will call your soul home, for even that belongs to him. It is a stark reminder that we are not made for this world, but for the next. Those little “asks” of God—surrender your money, surrender your time, surrender your freedom—prepare us to surrender our whole lives. That is why it is important to take those less profound sacrifices and make them intentional. “God, I give this to you because I love you, and I know you love me.” In this way, we may grow to realize that God is the source of every good that we have (ST I, q. 6, a. 4). And when he calls us home, it is nothing to fear. He is the greatest good for which we could ever hope.

When we finally recognize our smallness, our nothingness, our emptiness, it is then that God can fill us up with himself. “When we become full of God then we can give God to others, for from the fullness of the heart the mouth speaks” (Mother Teresa). God gave us the most precious gift of life and, one day, he will ask it back from us. Let us pray that, at that moment, we might be emptied of everything, and our heart filled with his love.

✠

Image: Quandary by Michael Belk from Journeys with the Messiah (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

Action and Procession

Is there a point to bringing the bread and wine to the priest during the Mass? Why not just keep them near the altar and save someone the trouble? The Acts of the Apostles actually has quite a bit to say about this. The book presents us with the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ. In the very first verse, Saint Luke says that his Gospel dealt with all that Jesus began to do and teach. But Jesus continues to act on earth through his Church, his Mystical Body. In Acts, the Church—the body of Apostles—performs the same actions that Christ performed on earth: preaching, praying, teaching, healing, forgiving sins, choosing apostles, and raising the dead.

Today, we do not commonly see the miraculous manifestations recorded in Acts, yet we see Christ continue his saving work in the acts of his faithful, from deeds of heroic charity to simple offerings of bread and wine. He invites us to participate in his work of salvation, not because he needs our help, but so that we may be perfected by entering into such work.

This grand drama is symbolically displayed in the offertory procession of the Mass. The General Instruction of the Roman Missal states that “it is a praiseworthy practice for the bread and wine to be presented by the faithful” (GIRM 73). As the words of the Mass remind us, bread and wine are “the work of human hands,” and so the faithful bring up their labors to the priest who is acting in the person of Christ the Head. One may object that the person bringing up the gifts did not actually make the bread or the wine. But as Saint Paul reminds us, “What do you have that you did not receive?” (1 Cor. 4:7). Everything that we have, we have from God. Any meritorious act we perform comes from the grace of Christ, received through his Church.

The offertory procession illustrates that Christ is both the origin and end of all that we do and offer to God. But there is an even deeper mystery here. The Mass transforms the offertory from a symbolic ritual gesture into an immersion into the very life of the Trinity. The bringing of the gifts has the practical end of providing the priest with the matter for the Sacrifice of the Mass. Here, we see that our participation in the Mass is a participation in Christ’s sacrifice on the cross to God the Father. And we are able to participate in the love between the Father and the Son by the gift of the Holy Spirit, who has filled us with the grace to be at Mass and participate in the offertory. In a simple and brief procession, we are caught up in the interior life of the Trinity. Stepping back, we see that the offertory procession reveals God as the source of all we are and all we do, God as the means of all we are and all we do, and God as the ultimate end of all we are and all we do. And all this, not because he needs us, but because he loves us. May we be reminded of this in our work and sacrifices throughout the week, which we offer to God at the Mass.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

Lenten Joy

We find ourselves this Lenten week surrounded by a trifecta of celebratory days—this is odd. Shouldn’t we be dour? Shouldn’t we be occupied with doing penance and mourning for our sins? Were not those ashes to set us on a path of dismal gloom until the great Easter Proclamation brings it to a happy end?

To answer these questions, let us use Our Lady’s words as our guide: “My spirit rejoices in God my Savior” (Lk 1:47).

These words are repeated each day in the Magnificat of the Divine Office, and follow shortly after the Gospel selection for this Saturday’s Solemnity of the Annunciation. Within this text is contained that notion celebrated in Laetare Sunday, St. Joseph’s feast day, and the Annunciation: rejoicing.

To rejoice in God is to rejoice in his glory, manifested in all of creation. God’s work of grace in each one of us most especially manifests this glory (ST I-II, q. 113, a. 9, ad 2). To celebrate Laetare Sunday then, is to rejoice in God’s grace which purifies our souls through Lenten prayer, fasting, and almsgiving in preparation for Easter.

The Solemnity of Saint Joseph observed on Monday gives us the opportunity to celebrate the example of the silent foster father of the Christ child. Saint Joseph sought not his own will, but the will of God—how else could he have accepted such a strange message from the angel in his dream? He leaves us this example: finding our fulfillment in God’s will regardless of how overwhelmed, fearful, or unworthy we might feel to take it up. Saint Joseph shows that rejoicing need not consist in external jubilation, but is also fittingly expressed in silent and fortitudinous acceptance of God’s providence.

Saint Joseph’s acceptance of God’s will is beautifully complimented and fulfilled by the Solemnity of the Annunciation this Saturday, celebrating that crucial event from the first chapter of Luke. When troubled by God’s providential plan for our lives, we join Mary in her awe and questioning—“how can this be?”—and we find the same consolation in Gabriel’s reply: “nothing will be impossible with God.” Mary’s example of “may it be done unto me according to your word” becomes our prayer of rejoicing in the face of what seems to be a burden too heavy to bear.

The execution of God’s will is not without its trials, but as Saint Peter reminds us “there is cause for rejoicing here” even in our suffering (1 Pet 1:6-7). Lent dares us to add “especially in these trials.” When the going gets tough, and God has given us what seems to be too much to handle, we rejoice in the grace that he gives us to carry it out. Lent and its penitential practices allow us to come to terms with our own brokenness and unworthiness, reminded by the ashes of Ash Wednesday that we are dust, mere mortals. Yet in all this, God has made himself known, that we may carry out his will in our lives.

✠

Image: Luca Giordano, The Dream of St. Joseph

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

God’s Suffering Shepherds

It does not take a genius to figure out that God has a thing for shepherds. From Abel to Jacob, Moses to David, and Amos to the shepherds of Bethlehem, the Lord has seen fit to select those who tend flocks as recipients of his favor. Often, these men of the fold were selected for special missions of drawing the people into a closer relationship with God, guiding them through the gate to divine pastures. This trend of divinely chosen pastors continued after the ascension of the Good Shepherd through his appointment of a chief shepherd (Jn 21:15-19) and further saintly shepherds in every age.

But a shepherd appointed by God is not cut from the same cloth as the romantic shepherd of Arcadia. Rather than lounging on sun-drenched hills, eating ripe grapes, and chasing fawns and nymphs, our shepherd endures scorching heat by day and frost by night as sleep flees from his eyes (Gen 31:40). He endures trials in guarding his charges and he himself draws closer to God through his suffering, being conformed to the Good Shepherd by taking up the yoke of the cross and finding his rest therein. Saint Patrick, the Shepherd of Ireland, was likewise conformed to the image of the Good Shepherd through his suffering and labor.

Though his father was a deacon and his grandfather a priest (at the time, married men could be ordained), Patrick, by his own admission, did not have faith as a young man. At sixteen, he was dragged away from his village in Britain by Irish raiders with other captives to endure punishment. He later acknowledged that they deserved such a fate “because we had gone away from God, and did not keep his commandments” (Confession of St. Patrick, 1). Enduring the bitter slavery of pagan Ireland as a swineherd, Patrick did not wallow in the depths to which he had sunk. Praying to the Lord became his consolation and he drew close to God while among the herds, in the woods, and on the mountains. Through his debasement and hardship his eyes were opened to God’s care for him even then and he returned to the Father he had turned his back upon (Confession, 2; cf Lk 15:15-20).

Even after escaping slavery, Patrick was not freed from trials and suffering. Called to the priesthood, he endured the trials of a stunted education, opposition by superiors towards his mission, and the calumnious accusation of a trusted friend. But, recognizing that he was like a stone that God had pulled from deep mud and placed upon a high wall, he endured all things to “shout aloud in return to the Lord for such great good deeds of his, here and now and forever, which the human mind cannot measure” (Confession, 12). Led by the Spirit, he returned to Ireland, the land of his captivity, no longer a lowly swineherd but a true shepherd according to the model of Christ.

The life of St. Patrick was a journey along the via crucis, from ignorance and ignominy to victory in Christ. This Way of the Cross became the model for the Irish people, who walked that road through poverty, calamity, persecution, and civil war. Following the way of St. Patrick, the Irish became “the people of the Lord. . . called children of God” (Confession, 36). Beyond simple asceticism, the Irish perfected the art of clinging to the Cross in imitation of the Lord. Not long after the death of St. Patrick, vocations began to flow from that tiny island as new shepherds were called from a people conformed to the crucified Christ. Many around the world have St. Patrick and his Irish shepherds to thank for their faith, and rightly celebrate that heritage today.

Here in the midst of Lent, let us learn from St. Patrick and take up our own crosses—especially those imposed upon us by circumstance—and follow the Good Shepherd. Let us draw near to Calvary, never shirking our burdens but always looking to Christ for aid. May we, through the intercession of St. Patrick, become true shepherds, faithful servants of the Lord.

✠

Image: Anton Mauve, Shepherd and Sheep

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

God at Rock Bottom

Bill Wilson, co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, wrote that “few people will sincerely try to practice the A.A. program unless they have hit bottom.” He found that utter desolation—rock bottom, as we call it—often incited alcoholics to admit their helplessness and surrender to a higher power.

So, then, is rock bottom a good or a bad thing? Without downplaying the awfulness of suffering and how horrific the lowest low may be, I propose that the very idiom hitting rock bottom indicates a hopeful reality.

Hitting rock bottom is not an experience known only to addicts, and it looks different from one situation to another. The cause could be the loss of a loved one, a severe illness, financial ruin, depression, or one of a hundred other calamities. In every case, however, the term rock bottom evokes the image of a dark and immensely deep hole in the ground. The afflicted person is at its floor; he is wounded, seemingly alone, and certainly unable to climb out on his own.

At the same time—and this is the hopeful part—the man at rock bottom is unable to go any further down. He has struck solid, immovable rock. The image is apt because when it seems like all the good things we hold dear have been dug out from beneath our feet (whether by ourselves or not), there is always at the bottom one foundational reality that cannot be disturbed or extracted: God, the very ground of our existence.

The Bible is replete with accounts of rock bottom, and the message is always the same: God is still God no matter what happens. Consider this passage from the Book of Habakkuk:

For though the fig tree blossom not

nor fruit be on the vines,

though the yield of the olive fail

and the terraces produce no nourishment,

though the flocks disappear from the fold

and there be no herd in the stalls,

yet will I rejoice in the Lord

and exult in my saving God (Hab 3:17-18).

You may lose your house, reputation, savings, good looks, hair, health, and even your loved ones, but you cannot lose God. Even if “the mountains fall into the depths of the sea” (Ps 46:2), you can take refuge in the eternal, unchanging Creator. While everything else does not have to exist, God simply is. He always has been and always will be; he made you and all the good things you may have lost. He is the reliable adamantine rock on which everything stands, and, in fact, he is the only support you need.

Some holy men and women endure a kind of spiritual rock bottom. Though in the state of grace and indeed very near to God, they feel utterly empty, especially when they try to pray. Like the Crucified Jesus, the Man of Sorrows, they may even cry, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Mt 27:46), and yet they also know in their bones that God is at their side, holding them in being. Thus, someone like St. Therese of Lisieux could write in her autobiography, “Spiritual aridity was my daily bread and, deprived of all consolation, I was still the happiest of creatures.” The saints know that God is near even in the darkness.

Someone at rock bottom likely may say, “It cannot get any worse.” Interpreted in one way, this is a bleak declaration of despair; in another, it is a sound confession of faith: As awful as things are now, I know they cannot get worse because “neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor present things, nor future things, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 8:38-39).

With faith, rock bottom is a sign of hope. When we fall into the depths—when our lives are at their worst—we do not descend forever into a black hole of meaninglessness. Instead, we meet God, who loves us and upholds us.

I love you, Lord, my strength, my rock, my fortress, my savior. My God is the rock where I take refuge; my shield, my mighty help, my stronghold (Ps 18:2-3).

✠

John Macallan Swan, The Prodigal Son

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

Everything Pertains to Love

The word “love” is cheap. Rather, it has been made cheap by a confused world that struggles to acknowledge the true desire of our hearts. In one moment, people declare love for their spouse or children, and in the very next moment express love for something like food, clothes, and the passing pleasures of this world. When everything seems to be worthy of love, love becomes less valuable.

While many have a confused sense of love, today the Church celebrates a great defender of true love: Saint Francis de Sales. Last December marked the 400th anniversary of his death, the day Pope Francis published an apostolic letter to commemorate the occasion.

Francis de Sales was a vastly influential figure in the history of Christian spirituality. His teaching can be summarized in his own words: “Everything pertains to love” (Treatise on the Love of God). He illustrates how everything in our lives involves love, for God is our everything, the same God who is love itself (1 John 4:7–21). He who numbered the vast sea of stars is also attentive to even the smallest hairs on our heads. What else could move the infinite God to care for such finite creatures except his infinite love? This God who has loved us so much, therefore, claims for himself the whole of our love: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might” (Deut 6:5).

Francis de Sales’s emphasis on the love of God offers an invaluable lesson for a world that fails to understand it. Admittedly, there are some differences between him and the Dominicans concerning some theological topics. We don’t need to go into detail about these differences, but our shared zeal for the salvation of souls should lead us to defend this Doctor of the Church and his teaching on the love of God. After all, the love that Francis de Sales emphasizes is none other than a share in the very life of God, he who is our beginning and end, who moves and orders all things, the desire of our hearts and object of our study, the one whom we proclaim in our preaching.

We can even acknowledge similarities between Francis de Sales and another Doctor of the Church who resonates with the Dominican mind and heart: our brother Saint Thomas Aquinas. Touching upon Aquinas’s teaching on the created order, to say with Francis de Sales that “everything pertains to love” means that everything in our lives is an opportunity to see God’s loving and gentle presence around us and within us. Through a beautiful manifestation of God’s providential care in creation, the life of love enables men and women—created in his image and likeness, and made sharers in the divine nature by grace—to be that same gentle presence of God to the world.

Francis de Sales, like Thomas Aquinas, also has an optimistic view of the human person, encouraging people to live the life God has laid before them out of love for them. Growth in virtue requires a dedication to truth, including the truth of who we are before God and the world. Yet, we can still be transformed in this life by grace. Rather than being reduced to a wretch, the soul is elevated by nothing other than God’s love.

Despite our weakness and sin, God has sent his Son out of love for us. This speaks to the Christ-centered character of the writings of Thomas Aquinas and Francis de Sales. Christ brings us to the Father to share in divine love. He is our model and teacher in the life of sanctity, while also being the very cause of this new life through his death on the cross. As one hymn puts it: “Love to the loveless shown, that they might lovely be” (Samuel Crossman, “My Song is Love Unknown,” 1664). Christ’s love on the cross shows that we are both loveable and are in fact loved. God continues to manifest this truth through the sacraments and the gift that is his Church.

The Dominican soul proclaims, without compromise, that our life and beatitude begin and end with God, and he is at work in everything in-between. Saint Francis de Sales proclaims a similar truth by saying that everything pertains to love. For if God is love, then our life and beatitude begin and end with love, and love is at work in everything in-between.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal