Category: Dominicana

So Much Time and So Little to Do

We always seem to be busy with so little time and so much to do. There always seems to be a list of tasks a mile long. Tasks get added to that list faster than we can complete them. Many of these tasks became impossible during the height of COVID. Locked down with nowhere to go and no one to see, some of us had free time for the first time since we were children.

As restrictions from the pandemic have loosened we may be thinking, “What a relief to be busy again!” We no longer have to figure out what to do when there is nothing that needs to be done. We have all our responsibilities back, responsibilities we’d missed because they were what gave structure and meaning to our lives. This is what the lives of adult, productive members of society are expected to look like, but the pandemic made us ask, “What do I do with my time when there’s nothing more to produce and all my responsibilities have been met?

The pandemic may have brought this question to the forefront, but it is the same question that parents have to ask once their children leave home, that the aging have to ask as they retire from work. What do we do with the time when we aren’t working? The question can, of course, be asked earlier. It can even be asked now. In fact, as Christians, the commandment to keep holy the Sabbath compels us to ask this question every week. How do I rest on Sunday? How we approach Sunday can then serve as a paradigm for how we approach other situations where we find ourselves with time on our hands.

Sunday is meant to be a day of rest, a day of leisure. It’s a day when we spend our time doing things other than work. The worship of God is an obvious feature. Sunday should be a time when we pray, especially at Mass. While spending time with God is the most important way of resting on Sunday, it is not the only way. Leisure time can be spent enjoying the company of friends and family. This happens at church, but also Sunday dinner or visits to grandparents. These can be occasions for conversations wherein we all become philosophers, asking the deep questions of life while unpressed for time. We can think about who we are and stop long enough to recognize God’s grace in our lives. These activities show that resting on Sunday and enjoying leisure consist in far more than the absence of labor. These are the times wherein the bare necessities of survival have been met and the full flourishing of human life is expressed. For an extended discussion on what constitutes leisure, I highly recommend Josef Pieper’s, Leisure: The Basis of Culture.

Learning to enjoy leisure helps us flourish as wayfarers, but it also prepares us for eternity. As we allow the rest of Sunday to penetrate more of our lives, we prepare for eternal life when that rest will be our whole life. We will have no responsibilities in heaven. The worries and anxieties of Martha will no longer press upon us (Lk 10:38-42). Every need will be satisfied. Heaven will be all leisure. Alongside Mary, we will sit at the feet of Jesus. There will be only one thing necessary: to join all the saints and angels in worshipping and praising God. We will have so much time and so much to do!

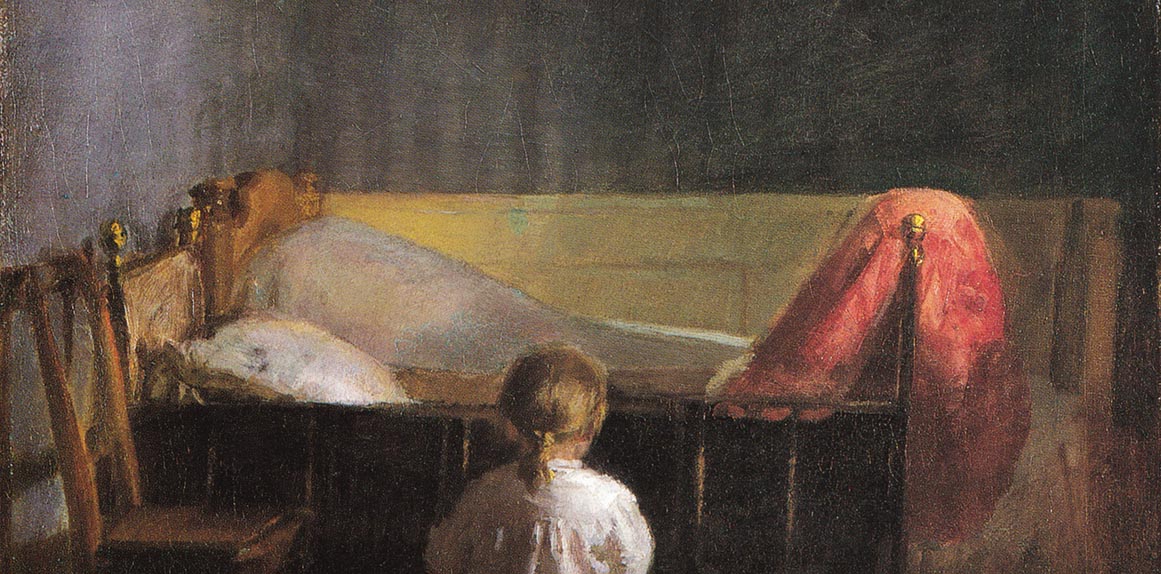

Image: Ivan Aivazovsky, Chumaks Leisure

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

Spiritual Hunger

At a convent of the Missionaries of Charity, my mother once made twelve bags of food to give to the homeless. She and the sisters then went to one of their usual spots in my hometown to hand out the bags of food, where there were never more than twelve people. However, upon arrival my mother discovered that there were, not twelve, but thirty-six homeless. Panicking, she told one of the sisters that they should go to another spot because there would not be enough bags of food for the crowd. The sister replied that my mother should start praying the Memorare prayer. So the sisters and my mother gathered the homeless together, prayed with them, and my mother proceeded to hand out the bags of food. When the last bag was handed out, everyone had a bag in their hands.

This happened when I was a child, and because of it, the Gospel story of the Feeding of the Five Thousand has always struck a special cord in my heart. This story also seems to have hit a special cord with the Gospel writers as well, given that it is the only miracle that is recounted in all four Gospels (Matt 14:13-21, Mark 6:34-44, Luke 9:10-17, John 6: 1-14).

The evangelists knew the significance of this miracle story not only because the miracle itself shows the powerful and providential care of Jesus for his people, but also because of what Jesus is pointing towards in this miracle. This miracle points us to the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, where Jesus’ sacrifice at Calvary is presented and where Jesus gives his Body and Blood to the Church as the healing food for our souls. In fact, the Book of Revelation even shows us that the same liturgy we celebrate in the Mass on earth is celebrated in Heaven. Each Mass, we should call to mind the communion of saints and angels all around us.

This all came together in the most beautiful way during one of my summer visits home. I was at mass right next to my mother. I watched as a packed congregation on a Saturday noon mass came up for communion. I couldn’t help but see us in the same light as the five thousand whom our Lord looked on with pity. Just as the five thousand were hungry for food, we were spiritually hungry for our Lord. As the apostles stood in the place of Jesus when they brought food to the five thousand, so the elderly priest stood in persona Christi as he slowly distributed the Eucharist from person to person along the communion rail.

Studying to be a priest of Jesus Christ, I can now see how, by reflecting on my mother’s miracle story, Jesus was using that event to point me to something higher. God will always look with pity on his children and will always provide priests of Jesus Christ to offer up the eternal sacrifice of Jesus for the sanctification of souls. Let us remember that every time we come to mass, we are entering into the sacrifice of Jesus for our sins and pray for a renewed spiritual hunger for Jesus in the Eucharist. Blessed are those called to the Supper of the Lamb.

Image: Fra Angelico, The Institution of the Eucharist

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

God is Not Far From Us

Pause for a minute and consider God.

Where does your mind take you?

I think for most of us the mind goes outward. We imagine God somewhere way out there beyond the stars and outer limits of the cosmos. From his seat faraway, he admires all he has made, and if we’re lucky, he might even look upon one of us with his favor.

This perspective is problematic.

First, God does not have a body; he is therefore not “in a place” or “far away.” “Where” is he then? Everywhere. Saint Paul teaches, “He is actually not far from each one of us, for ‘In him we live and move and have our being’” (Acts 17:27b-28a). I am because God is. Those things that are deepest in me—my life, my ability to will this or that, my very existence—are caused at all times and in all places by God’s innermost presence (cf. Thomas Aquinas, ST I, q. 8, a. 1). The hand holding a cup of coffee four feet from the ground is like God holding me in being. His “right hand holds me fast” (Ps 63:9 Grail), and he does not let go. “Where shall I go from your Spirit? Or where shall I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there! If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there!” (Ps 139:7-8). Wherever I am, there God is. Reason alone can even lead us to this awesome conclusion.

Beyond reason’s ambit, however, there lies a yet more profound truth about God’s nearness to the human soul. The Son reveals this truth: “If anyone loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him” (John 14:23). The Son reveals that God is a communion of Persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—who dwell together in perfect unity (cf. John 10:30). The Son reveals that God has invited us to share in this communion. The Son reveals that our sharing in this communion is made possible by God dwelling in our souls. When the soul is in a state of grace, God is inwardly present not only as sustainer and mover, but as light and fire making us capable of divine knowledge and love (Thomas Aquinas, ST I, q. 43., a. 3). The Father sends his Son, “the light of men” (John 1:4), to illuminate our minds with the truth of God. The Father and the Son send the Holy Spirit to enflame our hearts with the love of God (Rom 5:5; cf. John 14:16). And where the Son and the Spirit are, there too is the Father. The body becomes a temple for the Triune God (1 Cor 6:19).

It is not altogether wrong for the mind to go outward in contemplating God. God is wholly other. An infinite gap separates the Creator and the creature. My existence (the entire world’s existence!) is not necessary. God, on the other hand, is his own existence and he necessarily is: “I am who I am” (Ex 3:14). But precisely because of God’s supreme transcendence, he is most inwardly in all that is. The Christian at prayer contemplates a truth yet more marvelous. Gazing inwardly not to consider himself but to consider God, he might pray,

O my God, Trinity whom I adore, help me to forget myself entirely that I may be established in you as still and as peaceful as if my soul were already in eternity.

May nothing trouble my peace or make me leave You, O my Unchanging One, but may each minute carry me further into the depths of Your Mystery.

Give peace to my soul; make it Your Heaven, Your beloved dwelling and Your resting place. May I never leave You there alone but be wholly present, my faith wholly vigilant, wholly adoring, and wholly surrendered to Your creative Action

(Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity, Prayer to the Holy Trinity).

Image: Anna Ancher, Evening Prayer (Wikimedia Commons)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

The Virtue of Religion and the Pandemic

All of us experienced how the pandemic brought life to a halt last spring in a way that normalized what seemed unfathomable only a few weeks beforehand. For Catholics, among what became “normalized” was the dispensation from the obligation to attend Sunday Mass in order to slow the spread of the disease. Even now, things have not in many places returned to what they were pre-pandemic, and I imagine, given some of what I have read and conversations that I’ve had, that this must be a little confusing. How can Sunday Mass be dispensed from, unlike most moral obligations, if religious worship is so important?

Current societal tendencies that treat religion as superfluous to civic virtue make this even more confusing. The increasingly secular nature of Western societies has tried to affirm more and more strongly that “essential” life can get along without religious worship. Correspondingly, our governments have seen fit to suspend it as if it were any ordinary, potential COVID-superspreading-event.

The mistake is to see the obligation of religious worship as arbitrary—that is, seeing it as something that is only commanded—rather than seeing it as a way to give to God what is his due. This is similar to the way that we give other human beings their due through justice. Recall that morality is about happiness—human flourishing. To say, for instance, that you ought to act justly is to say that if you want to be happy then you need to act justly. You cannot fail to want to be happy, and so neglecting to act justly leads inevitably to deep, inner frustration. You’re obliged to act justly because God, by creating you with a certain nature that inextricably links acting justly to your being happy, has incorporated you into his governance that orders all creation to manifest his goodness.

Before moving on to religious worship, consider, for a moment, why acting justly is necessary for happiness with the following example. While walking outside one Saturday morning with a coffee in one hand and your eyes glued to the Summa Theologiae in the other, you crash through a sliding glass door. You then hire someone to replace the door with the agreement that you pay him $2,000. By replacing the door, the contractor gives you something of his own: his skilled labor. It’s up to you to make things equal again by compensating him for his work. If you don’t come through with the payment, you fail to relate to him properly. Yet because a human being is a social animal, you cannot flourish as a human being if you do not relate to other human beings and the broader society correctly. Paying him isn’t just about what he is owed; it’s also about who you are in relation to others.

When we consider religion as a virtue, we categorize it as a potential part of justice. Religion is a potential part of justice because, while it is similar to justice in most respects, it’s missing something. Through justice one renders to another what is due to him to establish equality. Through religion you render a debt to God for creating you, but you cannot reestablish equality like you did with the person who replaced your door. Nothing you give to God can equal what he has given to you.

Instead, it is sufficient to do what you can. Interiorly, you express religion through devotion and prayer. Devotion—the heart of religion—is the will to give yourself readily to what pertains to the service of God. Through prayer, you express your dependence on God by asking from him what you need.

We also express our devotion and prayers exteriorly through the exterior acts of religion. Not only are exterior acts signs for what is in the heart, but they also excite our hearts so that our devotion is more fervent (ST II-II, q. 81, a.7). One important exterior act is sacrifice. An exterior sacrifice expresses the interior sacrifice of the heart (Ps 51:18-19) where we hand over our souls to God and acknowledge him as our ultimate source of life and happiness (ST, II-II, q. 85, a. 2, corp.). God himself has taught us how to worship him properly and has provided for us through Christ’s sacrificial offering on the cross, which we offer to God through the Mass. He has positively commanded us to worship him in this way.

With all of that being said, religion is part and parcel of an integral human life, and without it that life would become shallow. Worship—both interior and exterior—is necessary for us to express our subordination to and dependence on God in everything. We need it to relate to God properly. It is necessary for us to do this through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, that supreme form of worship God has provided for us. It is necessary for us to observe the Lord’s Day, in keeping with Divine Law, to remind us that our final rest is in God. The bishops relaxed part of the Church’s discipline that regulates how these were observed for a time on account of a public emergency, but they never pretended to do away with our inextricable need for public worship.

Image: Photo by Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

Why the Chair of Saint Peter Will Never Break

Few experiences are as unexpectedly unnerving—and embarrassing—as settling yourself into a chair only to have it buckle and break, dropping you flailing on the floor. Chairs are supposed to be secure and trustworthy, things that hold us up and protect us. Most chairs will eventually fail; one won’t. Today we celebrate that sturdiest of chairs, the Chair of St. Peter.

While the physical Chair of St. Peter, magnificently encased in bronze by Bernini, has proved surprisingly durable for a sixth-century piece of wooden furniture, the spiritual stability it represents is eternally rock solid. The pope’s teaching authority is a gift Christ gives to the Church which, like a good chair, gives stability and security to our faith.

What prevents the pope’s chair from collapsing, however, is not bronze, but the true rock: “And the rock was Christ” (1 Cor 10:4). Jesus Christ is the true foundation of the Church’s faith, “a stone that has been tested, a precious cornerstone as a sure foundation; whoever puts faith in it will not waver” (Isa 28:16). Peter’s office calls out to us “Come to him, a living stone, rejected by human beings but chosen and precious in the sight of God” (1 Pet 2:4). Peter became a rock of faith because he first came to that living stone.

But Peter wasn’t always so solid or stable. His faith had to be compacted and molded and then reinforced. When Peter stepped out of his boat to join Jesus walking on the water, the waves of disbelief beat down his weak faith. Yet he knew to call out to the one who could steady him, grasp his hand, and set his feet on solid ground (Matt 14:22–33).

Before his Passion, Jesus told Peter “Simon, Simon, behold Satan has demanded to sift all of you like wheat, but I have prayed that your own faith may not fail; and once you have turned back, you must strengthen your brothers” (Luke 22:31–32). When Jesus prayed that Peter’s faith would arise from the ashes of his denial and reinforce the faith of the Church, the Lord assured us he would accomplish it. Jesus promised to make the shifting sands of Peter’s faith into a solid bedrock for the Church.

That promise of Christ holds good for all the popes from Peter to Francis. Their ability to steady the faith of others doesn’t depend on the strength of their own wisdom but on the word of Christ. Even if the chair seems to wobble—as during the Renaissance, for example—the office of the pope has never given way to error about God. We see this exemplified in the life of Peter, the first pope. He could fortify his brothers because he didn’t just follow what he wanted or thought right. Instead, he was open to being led where he did not initially want to go, stretching out his hands to be led by Christ (John 21:15–19). Saved from the waters of doubt and disbelief he can reach out his own hand to strengthen his brothers and secure their faith. Regardless of who is pope, it is Christ who stretches out the pope’s hand to draw us to know and love God.

Dominican priest and theologian Father Antonin Gilbert Sertillanges once wrote, “Towards Rome ever goes the road of the heart and the mind; it can always be traversed; the true faithful traverse it daily.” We go to Peter to find Christ. He leads us to know and believe in him, not as the world thinks of him—“Who do men say that the Son of man is?” (Matt 16:13)—but as he really is. This is why we celebrate Peter’s chair. We don’t have to fear the embarrassment of this chair collapsing beneath the weight of confused ideologies and worldly distortions. When our hearts and minds traverse the way to Rome, they can settle down secure.

Image: Photo by Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal