Tag: Theology

Bringing His Knowledge to the World

St. Dominic was inspired by the conviction that knowledge is the surest path to Christ. He established his order to ensure that those who understood Christ most deeply could share their understanding with those needing light. Communally, all souls would grow together on God’s enlightened path and enjoy the eternal rewards of faithfulness.

The Dominican House of Studies (DHS) exists to perpetuate the mission of St. Dominic. Our revered institution receives learned individuals seeking to better understand Christ’s role in their lives, increases their knowledge, and then sends them into the world so that they may bring more souls to Him.

Current DHS doctoral student Father Thomas Aquinas Pickett, OP, embodies our mission. A self-described “cradle Catholic,” he was born to faithful parents who ensured he remained mindful of the worth and purpose of his soul.

Coupling the foundations of his parents’ teachings and the spiritual gift of intellectual curiosity bestowed upon him by God, Father Pickett has embarked upon a life’s quest for understanding. Acquiring knowledge is edifying for him, but his greatest desire is to share this knowledge to edify others.

Gaining and Sharing the Light

While spirituality and faithfulness were always present in his home, the world outside those four walls was much different.

“I grew up in an area where there are a lot of non-Catholics,” he recounted, “and they would either ask me questions or challenge me on certain things. It was imperative for me to articulate my faith. There were many misconceptions I had to correct.”

While he did not understand how people could lack such clarity, he learned that the perfection of God’s truth provided every answer he would ever need. This clarity set him on the path of a relentless pursuit of the light of Christ.

A Cradle Catholic’s Quest

As he matured, Father Pickett was most intrigued by the elements of his faith that he least understood.

“I was always intrigued by the mysteries of faith, not just to absorb what I was taught, but to question, understand, and challenge the tenets of my faith,” he reflects.

This profound curiosity led him to explore the depths of theological and philosophical questions as a philosophy student in his college years. This was particularly evident in his desire to understand prayer and its relationship with God’s plan.

“I started wondering if God knows everything already,” he shared, “why are we talking to Him? Or, if everything is following His plan, are we trying to change it when we’re praying? What does prayer actually do?”

In this period of questioning, he discovered the works of St. Thomas Aquinas, which profoundly transformed his understanding of prayer, God’s providence, and the essence of truth.

The Dominican Way

The Dominican Order’s commitment to preaching and teaching provided the perfect pathway for deepening his pursuit.

“St. Thomas Aquinas, with his analytical approach to theology, offered a framework that truly resonated with me,” he stated. “The Dominican Order’s charism of contemplation and sharing the fruits of that contemplation was exactly what I was looking for.”

This pursuit was not merely intellectual but a spiritual quest to live out the truths he discovered.

Formation at the Dominican House of Studies

The Dominican House of Studies has played a crucial role in refining both his intellect and spirituality. Here, he has learned that to share Christ effectively with others, he must first embody the Gospel’s truth in his own life.

“Theology at DHS is not just a subject of study but a way of life that demands a commitment to holiness,” he recalled.

“I remember a professor telling me very explicitly early on that theology can’t just be an academic discipline,” he continued, “to be a theologian requires knowing, loving, and serving Christ. Without that, you are doing an academic exercise, but without the grace necessary to truly understand what you are learning.”

Spreading the Word

Upon completing his doctorate at DHS, Father Pickett will serve as a professor at the Dominican School of Philosophy and Theology in Berkeley, California. His deep knowledge and inspirational message will edify and enlighten others dedicated to holy service. His students will share the Holy Gospel armed with the truths they need to bring souls unto Christ.

As Father Pickett prepares to teach and form future Dominicans and evangelists, his story stands as a powerful witness to a faith that seeks understanding—a faith unwilling to settle for easy answers but instead dives deep into the Gospel’s heart.

“My journey from a curious child to a dedicated friar and theologian highlights the communal aspect of our pursuit of Christ. It’s not just about seeking answers for ourselves but for the entire world,” he explained.

A Beacon of Light for the World

His narrative is a vivid reminder that the path to Christ is both deeply personal and inherently communal. It underscores the importance of seeking Christ for personal enlightenment and as a mission to bring truth and clarity to others.

“I hope my story serves as a beacon of light for those navigating the seas of doubt and confusion, offering a path that leads to truth, clarity, and ultimately, to Christ Himself,” he concludes.

Through his journey, we are reminded of the transformative power of faith that seeks understanding, the importance of living the truths we discover, and the profound impact of sharing those truths with the world. His life is a living embodiment of the Dominican mission, illuminating the path to Christ in a world in desperate need of truth.

If reading Father Pickett’s story inspires you to support our mission to share refined knowledge of Christ with the world, please click here to support the Dominican House of Studies.

How the Dominican House of Studies Empowers Teachers to Send His Light Into the World

It could be argued that there is no higher call than providing young souls with the Light of Christ so that they may draw on that power throughout their lives. Imparting the ability to discern good from evil is invaluable in a world where the differences between the two are increasingly blurred.

Dominican House of Studies’ alumna Sister Maria Catherine heeds this call. As a Dominican Sister of St. Cecilia, she instructs third through eighth graders daily at St. Mary’s Catholic School, a parish school in South Carolina.

Using lessons and instructional methods she honed and acquired at the Dominican House of Studies, she guides young people to an understanding of their value and purpose as children of Christ.

Formation at the DHS

Growing the faith of children and supporting families in their mission to bring Christ into their hearts is the mission of the Sisters of St. Cecilia. Women who enter the Nashville Dominican Sisters either have a bachelor’s degree in education or earn one after joining the community. To increase their effectiveness as teachers, the sisters remain devoted to studying and growing their knowledge of Christ throughout their religious lives.

Sister Maria Catherine came to the Dominican House of Studies to earn her master’s degree through an intensive five-year summer program. The Friars developed the program for sisters to study and understand the thoughts and teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas in the Summa Theologiae.

“I had already studied St. Thomas somewhat,” Sister Maria Catherine recounted, “but studying that with the Friars really brought me to understand Thomas’s love for scripture and to learn how to walk with my brother Thomas in a deeper understanding of the truth that the Lord’s giving in the scriptures.”

Understanding St. Thomas’s vision helped her see the whole plan of God and comprehend the richness of the life of holiness in Jesus that the Lord has in store for each of us. Gaining this deep personal knowledge has been foundational in Sister Maria Catherine’s continued devotion to God and her mission.

“The Friars taught me how to take St. Thomas as a guide in understanding myself,” she said, “and enriching my own vocation of belonging to Christ enhanced my service to the families and children I teach. I learned how St. Thomas explains the truth of the person so clearly, and it has enabled me to articulate the truth more clearly and guide young souls to the joys of Christ.”

Teaching the Children

Sister Maria Catherine finds great blessing in shining the light and directing young people to overcome the distractions today’s world bombards them with. All the technology they use, the entertainment they consume, and the activities they participate in to fill their time do not fill the hole in her students’ hearts.

“These kids never have the time to stop and see the bigger picture,” she said. “They never get a chance to ponder their direction and see the true beauty of life. The world has filled them with a need to have their time constantly filled with empty things, and there is a lack of seeing that every moment can have meaning if we allow Christ to give light, meaning, and joy to every minute.”

Empowering students to grasp this truth is no small feat. Sister Maria Catherine blends the knowledge her students have been given by loving parents in their home with the enlightenment she has acquired at the Dominican House of Studies and throughout her religious life. Through her joy and zeal, students move from knowing who Christ is to developing a personal relationship with Him. Establishing that relationship forms a greater understanding of their destiny in God and with God.

“We heavily focus on the magnanimity of the soul,” she said. “We make sure they understand that the Lord has a call for them and a purpose for them and that responding to His call has an impact on the whole world. It’s not just that Jesus loves them. It’s that He has a mission for them. He’s using them in ways they can’t even see. They light up when they come to understand that their life has a divine purpose.”

The Reach of Her DHS Formation

Gifted educators teach in the manner they learn. At the Dominican House of Studies, Sister Maria Catherine experienced firsthand the power of reading, discussing, and growing in knowledge as a group. During her studies, she realized that the discussions and questions that came up with her Sisters were similar to those of her students.

The Dominican Sisters of St. Cecilia often incorporate the Socratic method into their teaching, and the growth Sister Maria Catherine experienced through this style at the DHS refined her technique and purpose for employing it in her classroom.

“I really like to teach kids how to read a text in depth and learn how to analyze and dissect something meaningful and substantial,” she stated. “Then I have them discuss it with their peers. They learn to trust that they can think, reason, and know the truth of their faith.”

The impact of this knowledge is more substantial than bringing one young soul to Christ.

“It’s definitely effective for their personal conversion,” Sister Maria Catherine continues, “but it also teaches them how to evangelize and bring more souls to the Joy and Light of Christ.”

Why The Work of the Dominican House of Studies Matters

St. Dominic believed that God wanted truth and knowledge to be the typical path to salvation and wanted all to have it. The Dominican House of Studies continues St. Dominic’s mission by equipping Sisters and Friars with the tools they need to evangelize Christ’s Light to the world.

“I love the imagery of St. Dominic with his torch setting the world on fire with the love of Christ,” Sister Maria Catherine shared. “I am grateful the Lord saw fit to invite me to DHS and be a part of His process. Refining my knowledge of His Word and strengthening my bond with Him has prepared me to bring as many souls to Him as possible by spreading His joy and filling the holes in the hearts of the children I teach.”

Sister Maria Catherine moves young people to eschew the hollow distractions of the world and instead fill their hearts and minds with the solid Word of Christ. Those who receive His Word will influence others to seek the same joy and happiness.

Consider yourself and your circle. You may not have the same opportunity to evangelize Christ’s love to young people as this great sister and DHS alumna does, but pray for His guidance in finding opportunities to bring more souls to Him in any way you can.

Fr. Basil Cole, O.P. named Master of Sacred Theology

Emeritus Professor Father Basil Cole, O.P., was recently given one of the highest honors of the Dominican Order. He was named a Master of Sacred Theology and now follows in a long line of great theologians going back to the founding of the Order. With overwhelming support, the 2022 quadrennial Provincial Chapter of the Province of St. Joseph nominated Father Cole to the Master of the Order for this honor. After consulting other experts, the Master, Father Gerard Francisco Timoner, O.P. made Father Cole a Master of Sacred Theology on October 17th.

During vespers on Wednesday, January 10th in the Chapel of the Priory of the Immaculate Conception, the decree naming Father a Master was read and the insignia of the title were conferred. First, he received the ring as a sign that he has been espoused by Wisdom. In keeping with tradition, the ring is set with an amethyst stone. It also bears the shields of both the Dominican Order and the Province of St. Joseph. He was then given the black and red four-peaked biretta, which is a symbol of Masters of Theology, and is often worn during solemn academic ceremonies.

A festive dinner with guests and the community followed.

On Thursday, January 11th Father Cole delivered a magisterial lecture in Aquin Hall to an audience of nearly one hundred people. The title of his lecture was “Spiritual Beauty and the Challenge of the Life of Virtue.” Following closely the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, the singular Master of Theology, Father Cole elucidated the importance of the arts—particularly literature, painting, and music—in helping a person grow in virtue.

On receiving the honor, Father Cole noted that the honor belonged not just to him, but to all those who’ve encouraged him, supported him, and to all of his students over the years. He continues to write and publish. He has a number of manuscripts preparing for publication.

Eucharistic Concomitance and the Resurrection

When we speak about Jesus, the “Lord of glory” who “became flesh and dwelt among us” (1 Cor 2:8; John 1:14), we often use rare words or phrases specially crafted to express the mystery of his being. Hypostatic union is one of them: the two natures of Christ are united in his one person. Consubstantial appears every Sunday in the Creed: the Father and the Son are one in substance. We would also do well to restore concomitance to our collective vocabulary. The doctrine of concomitance, taught in 1551 by the Council of Trent, captures a marvelous truth about the Eucharist and thus about Christ who “being raised from the dead will never die again” (Rom 6:9). During our nation’s Eucharistic revival, thinking through concomitance can and will inflame our devotion to Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament.

At first glance, concomitance may seem simple. The Son of God becomes fully present—Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity—under both sacramental species used at Mass. What used to be bread and what used to be wine are equally, substantially changed into our Lord by his own divine words. Only the species or “forms” of bread and wine remain. Therefore, according to concomitance, we do not receive “more” when we receive from both the chalice and the host, nor “less” if only from one. This doctrine is practically important especially when both forms are newly offered (or newly discontinued) for the communion of the faithful. In Holy Communion, the whole Jesus is always received under either form.

If concomitance is true, then why have two forms? The priest consecrates bread and wine separately in imitation of Christ, who did so at the Last Supper and told us to do what he had done. Christ gave his Body and Blood to the disciples separately precisely because this Body and Blood would soon be separated for them, in the free outpouring of his redemptive love. The Mass is a sacrifice because it is this one sacrifice, the unique sacrifice on the Cross. The daily offering of sacramentally separate Body and Blood reveals and makes present the one sacrifice of Calvary, so that we may all join in Jesus’ self-offering to the Father.

While making present the awesome mystery of the Cross, the Mass never turns back the clock on our redemption. For Christ has only one body, and in the Eucharist precisely this human body is signified and offered. On the cross, Jesus’ body and blood were separated. In death, his human soul was separated from both. But on the third day, for his and our glory, the one body of our Savior was raised and exalted, in the real re-union of his real humanity. This body ascended into heaven and sits at the Father’s right hand. And it is this body that Christ offers us at every Mass.

Concomitance signals this reality. We receive the Body and the Blood separately, commemorating the Passion of our Lord. But we know by faith that Jesus Christ, the eternal Word with his assumed human nature whole, resplendent, and never more alive, now dwells forever in the glory to which he calls us. We cannot hear enough that it is this one, risen Body that we receive in Holy Communion, or that it is to this glory that it will lead us.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

My Grace is Sufficient for You

“All of this is because a fisherman died here,” said my then friend, now fellow Dominican Brother, as we stood atop St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. It is true. The fisherman from Galilee, buried 450 feet below us, was certainly not wise by human standards, powerful, nor well born. (1 Cor 1:26). He was not preserved from serious sins like Mary, John the Baptist, or John the Evangelist. This was the disciple who denied Our Lord three times (Luke 22:54–61). Nonetheless, our Lord still called Simon son of Jonah. He built his Church on him and gave him the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven (Matt 16:17–18). He told him to feed his sheep and foretold his martyrdom on the Vatican hill (John 21:15–19). This calling and the grace our Lord gave to this weak fisherman turned him into a strong fisher of men, and shepherd of souls.

From the top of St. Peter’s we could also see another massive basilica down the Tiber. This one does not house the bones of a fisherman. Rather, it is built over the tomb of a radical first century pharisee (Phil 3:4–6). A man not even fit to be called an apostle because he persecuted the Church of God (1 Cor 15:9). A man who consented to the execution of St. Stephen (Acts 8:1) and tried to destroy the Church (Gal 1:13). Yet this man, this sinner, was chosen by God’s grace. This man was struck down on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:1–9), and encountered the Risen Lord (Gal 1:12). These two men, one uneducated and ordinary (Acts 4:13), and the other an enemy of God (Rom 5:10), were reconciled to God! They became Peter, the rock on which the Church is built (Matt 16:17) and Paul, God’s chosen instrument (Acts 9:15).

These two sinners-turned-saints are useless on their own. Peter is not the rock of his own Church; he is the rock on which Christ builds his Church. So too Paul, as a chosen instrument of grace, is nothing without someone to use the instrument, namely Christ. These two men remind us that without God we can do nothing (John 15:5). For these men are apostles only because Jesus is “the apostle and high priest of our confession” (Heb 3:1). They are bishops and shepherds only because Jesus is “the shepherd and bishop of our souls” (1 Pet 2:25).

Despite their sins, despite their mediocrity, God did amazing things with these two men. God made them like Jesus. God used their suffering to “fill up what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ on behalf of his body, which is the church”(Col 1:24). He made them a spectacle to the world, being hungry and thirsty, naked, roughly treated, homeless, and toiling (1 Cor 4:11–12). He made them like Jesus who had nowhere to rest his head (Matt 8:20). God took these men and conformed them to Jesus Christ, using them to bring his gospel to the ends of the earth (Ps 19:4). This conformity to Jesus went deep; he even gave Paul his marks on his body (Gal 6:17).

In the end this transformation, begun on the beach in Galilee and on the road to Damascus, ended in Rome. Peter was so configured to the cross of Christ, that he, like the savior, was crucified. So too Paul was executed in the same city by beheading. However, their martyrdom was not merely the result of their work in the Lord’s vineyard. The grace of final perseverance was a gift, but it was not only a gift for these blessed Apostles. This final grace given to Peter and Paul extends to you and me! The same grace God used to save them, he now uses through them to save us. So that just as their voices went out through all the world in their earthly life, their prayers in heaven now bring us the graces of Jesus Christ!

Tomorrow the Church celebrates the principal feast of these heavenly patrons. Let us turn to them as our fathers and sources of Sacred Scripture and the Tradition of the Church. But more than that, let us turn to them because they are reigning in heaven! The rock still supports the Church, and the chosen instrument still intercedes for men.

Photo by David Iliff (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal on June 28, 2022

God is Not Far From Us

Pause for a minute and consider God.

Where does your mind take you?

I think for most of us the mind goes outward. We imagine God somewhere way out there beyond the stars and outer limits of the cosmos. From his seat faraway, he admires all he has made, and if we’re lucky, he might even look upon one of us with his favor.

This perspective is problematic.

First, God does not have a body; he is therefore not “in a place” or “far away.” “Where” is he then? Everywhere. Saint Paul teaches, “He is actually not far from each one of us, for ‘In him we live and move and have our being’” (Acts 17:27b-28a). I am because God is. Those things that are deepest in me—my life, my ability to will this or that, my very existence—are caused at all times and in all places by God’s innermost presence (cf. Thomas Aquinas, ST I, q. 8, a. 1). The hand holding a cup of coffee four feet from the ground is like God holding me in being. His “right hand holds me fast” (Ps 63:9 Grail), and he does not let go. “Where shall I go from your Spirit? Or where shall I flee from your presence? If I ascend to heaven, you are there! If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there!” (Ps 139:7-8). Wherever I am, there God is. Reason alone can even lead us to this awesome conclusion.

Beyond reason’s ambit, however, there lies a yet more profound truth about God’s nearness to the human soul. The Son reveals this truth: “If anyone loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him” (John 14:23). The Son reveals that God is a communion of Persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—who dwell together in perfect unity (cf. John 10:30). The Son reveals that God has invited us to share in this communion. The Son reveals that our sharing in this communion is made possible by God dwelling in our souls. When the soul is in a state of grace, God is inwardly present not only as sustainer and mover, but as light and fire making us capable of divine knowledge and love (Thomas Aquinas, ST I, q. 43., a. 3). The Father sends his Son, “the light of men” (John 1:4), to illuminate our minds with the truth of God. The Father and the Son send the Holy Spirit to enflame our hearts with the love of God (Rom 5:5; cf. John 14:16). And where the Son and the Spirit are, there too is the Father. The body becomes a temple for the Triune God (1 Cor 6:19).

It is not altogether wrong for the mind to go outward in contemplating God. God is wholly other. An infinite gap separates the Creator and the creature. My existence (the entire world’s existence!) is not necessary. God, on the other hand, is his own existence and he necessarily is: “I am who I am” (Ex 3:14). But precisely because of God’s supreme transcendence, he is most inwardly in all that is. The Christian at prayer contemplates a truth yet more marvelous. Gazing inwardly not to consider himself but to consider God, he might pray,

O my God, Trinity whom I adore, help me to forget myself entirely that I may be established in you as still and as peaceful as if my soul were already in eternity.

May nothing trouble my peace or make me leave You, O my Unchanging One, but may each minute carry me further into the depths of Your Mystery.

Give peace to my soul; make it Your Heaven, Your beloved dwelling and Your resting place. May I never leave You there alone but be wholly present, my faith wholly vigilant, wholly adoring, and wholly surrendered to Your creative Action

(Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity, Prayer to the Holy Trinity).

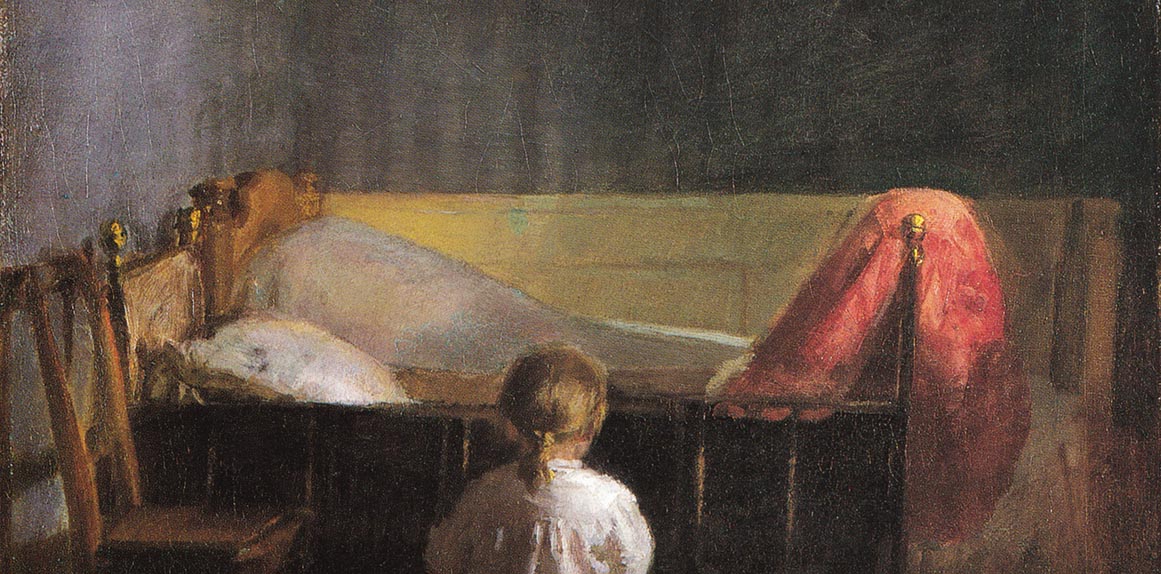

Image: Anna Ancher, Evening Prayer (Wikimedia Commons)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

The Virtue of Religion and the Pandemic

All of us experienced how the pandemic brought life to a halt last spring in a way that normalized what seemed unfathomable only a few weeks beforehand. For Catholics, among what became “normalized” was the dispensation from the obligation to attend Sunday Mass in order to slow the spread of the disease. Even now, things have not in many places returned to what they were pre-pandemic, and I imagine, given some of what I have read and conversations that I’ve had, that this must be a little confusing. How can Sunday Mass be dispensed from, unlike most moral obligations, if religious worship is so important?

Current societal tendencies that treat religion as superfluous to civic virtue make this even more confusing. The increasingly secular nature of Western societies has tried to affirm more and more strongly that “essential” life can get along without religious worship. Correspondingly, our governments have seen fit to suspend it as if it were any ordinary, potential COVID-superspreading-event.

The mistake is to see the obligation of religious worship as arbitrary—that is, seeing it as something that is only commanded—rather than seeing it as a way to give to God what is his due. This is similar to the way that we give other human beings their due through justice. Recall that morality is about happiness—human flourishing. To say, for instance, that you ought to act justly is to say that if you want to be happy then you need to act justly. You cannot fail to want to be happy, and so neglecting to act justly leads inevitably to deep, inner frustration. You’re obliged to act justly because God, by creating you with a certain nature that inextricably links acting justly to your being happy, has incorporated you into his governance that orders all creation to manifest his goodness.

Before moving on to religious worship, consider, for a moment, why acting justly is necessary for happiness with the following example. While walking outside one Saturday morning with a coffee in one hand and your eyes glued to the Summa Theologiae in the other, you crash through a sliding glass door. You then hire someone to replace the door with the agreement that you pay him $2,000. By replacing the door, the contractor gives you something of his own: his skilled labor. It’s up to you to make things equal again by compensating him for his work. If you don’t come through with the payment, you fail to relate to him properly. Yet because a human being is a social animal, you cannot flourish as a human being if you do not relate to other human beings and the broader society correctly. Paying him isn’t just about what he is owed; it’s also about who you are in relation to others.

When we consider religion as a virtue, we categorize it as a potential part of justice. Religion is a potential part of justice because, while it is similar to justice in most respects, it’s missing something. Through justice one renders to another what is due to him to establish equality. Through religion you render a debt to God for creating you, but you cannot reestablish equality like you did with the person who replaced your door. Nothing you give to God can equal what he has given to you.

Instead, it is sufficient to do what you can. Interiorly, you express religion through devotion and prayer. Devotion—the heart of religion—is the will to give yourself readily to what pertains to the service of God. Through prayer, you express your dependence on God by asking from him what you need.

We also express our devotion and prayers exteriorly through the exterior acts of religion. Not only are exterior acts signs for what is in the heart, but they also excite our hearts so that our devotion is more fervent (ST II-II, q. 81, a.7). One important exterior act is sacrifice. An exterior sacrifice expresses the interior sacrifice of the heart (Ps 51:18-19) where we hand over our souls to God and acknowledge him as our ultimate source of life and happiness (ST, II-II, q. 85, a. 2, corp.). God himself has taught us how to worship him properly and has provided for us through Christ’s sacrificial offering on the cross, which we offer to God through the Mass. He has positively commanded us to worship him in this way.

With all of that being said, religion is part and parcel of an integral human life, and without it that life would become shallow. Worship—both interior and exterior—is necessary for us to express our subordination to and dependence on God in everything. We need it to relate to God properly. It is necessary for us to do this through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, that supreme form of worship God has provided for us. It is necessary for us to observe the Lord’s Day, in keeping with Divine Law, to remind us that our final rest is in God. The bishops relaxed part of the Church’s discipline that regulates how these were observed for a time on account of a public emergency, but they never pretended to do away with our inextricable need for public worship.

Image: Photo by Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

Why the Chair of Saint Peter Will Never Break

Few experiences are as unexpectedly unnerving—and embarrassing—as settling yourself into a chair only to have it buckle and break, dropping you flailing on the floor. Chairs are supposed to be secure and trustworthy, things that hold us up and protect us. Most chairs will eventually fail; one won’t. Today we celebrate that sturdiest of chairs, the Chair of St. Peter.

While the physical Chair of St. Peter, magnificently encased in bronze by Bernini, has proved surprisingly durable for a sixth-century piece of wooden furniture, the spiritual stability it represents is eternally rock solid. The pope’s teaching authority is a gift Christ gives to the Church which, like a good chair, gives stability and security to our faith.

What prevents the pope’s chair from collapsing, however, is not bronze, but the true rock: “And the rock was Christ” (1 Cor 10:4). Jesus Christ is the true foundation of the Church’s faith, “a stone that has been tested, a precious cornerstone as a sure foundation; whoever puts faith in it will not waver” (Isa 28:16). Peter’s office calls out to us “Come to him, a living stone, rejected by human beings but chosen and precious in the sight of God” (1 Pet 2:4). Peter became a rock of faith because he first came to that living stone.

But Peter wasn’t always so solid or stable. His faith had to be compacted and molded and then reinforced. When Peter stepped out of his boat to join Jesus walking on the water, the waves of disbelief beat down his weak faith. Yet he knew to call out to the one who could steady him, grasp his hand, and set his feet on solid ground (Matt 14:22–33).

Before his Passion, Jesus told Peter “Simon, Simon, behold Satan has demanded to sift all of you like wheat, but I have prayed that your own faith may not fail; and once you have turned back, you must strengthen your brothers” (Luke 22:31–32). When Jesus prayed that Peter’s faith would arise from the ashes of his denial and reinforce the faith of the Church, the Lord assured us he would accomplish it. Jesus promised to make the shifting sands of Peter’s faith into a solid bedrock for the Church.

That promise of Christ holds good for all the popes from Peter to Francis. Their ability to steady the faith of others doesn’t depend on the strength of their own wisdom but on the word of Christ. Even if the chair seems to wobble—as during the Renaissance, for example—the office of the pope has never given way to error about God. We see this exemplified in the life of Peter, the first pope. He could fortify his brothers because he didn’t just follow what he wanted or thought right. Instead, he was open to being led where he did not initially want to go, stretching out his hands to be led by Christ (John 21:15–19). Saved from the waters of doubt and disbelief he can reach out his own hand to strengthen his brothers and secure their faith. Regardless of who is pope, it is Christ who stretches out the pope’s hand to draw us to know and love God.

Dominican priest and theologian Father Antonin Gilbert Sertillanges once wrote, “Towards Rome ever goes the road of the heart and the mind; it can always be traversed; the true faithful traverse it daily.” We go to Peter to find Christ. He leads us to know and believe in him, not as the world thinks of him—“Who do men say that the Son of man is?” (Matt 16:13)—but as he really is. This is why we celebrate Peter’s chair. We don’t have to fear the embarrassment of this chair collapsing beneath the weight of confused ideologies and worldly distortions. When our hearts and minds traverse the way to Rome, they can settle down secure.

Image: Photo by Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal