- Home

- Latest Content

- The Virtue of Religion and the Pandemic

The Virtue of Religion and the Pandemic

Recall that morality is about happiness—human flourishing. To say, for instance, that you ought to act justly is to say that if you want to be happy then you need to act justly.

by

Br. Nicholas Hartman, O.P.

on

March 21, 2021

in

Dominicana

Theology Virtue Virtue & Moral Life

All of us experienced how the pandemic brought life to a halt last spring in a way that normalized what seemed unfathomable only a few weeks beforehand. For Catholics, among what became “normalized” was the dispensation from the obligation to attend Sunday Mass in order to slow the spread of the disease. Even now, things have not in many places returned to what they were pre-pandemic, and I imagine, given some of what I have read and conversations that I’ve had, that this must be a little confusing. How can Sunday Mass be dispensed from, unlike most moral obligations, if religious worship is so important?

Current societal tendencies that treat religion as superfluous to civic virtue make this even more confusing. The increasingly secular nature of Western societies has tried to affirm more and more strongly that “essential” life can get along without religious worship. Correspondingly, our governments have seen fit to suspend it as if it were any ordinary, potential COVID-superspreading-event.

The mistake is to see the obligation of religious worship as arbitrary—that is, seeing it as something that is only commanded—rather than seeing it as a way to give to God what is his due. This is similar to the way that we give other human beings their due through justice. Recall that morality is about happiness—human flourishing. To say, for instance, that you ought to act justly is to say that if you want to be happy then you need to act justly. You cannot fail to want to be happy, and so neglecting to act justly leads inevitably to deep, inner frustration. You’re obliged to act justly because God, by creating you with a certain nature that inextricably links acting justly to your being happy, has incorporated you into his governance that orders all creation to manifest his goodness.

Before moving on to religious worship, consider, for a moment, why acting justly is necessary for happiness with the following example. While walking outside one Saturday morning with a coffee in one hand and your eyes glued to the Summa Theologiae in the other, you crash through a sliding glass door. You then hire someone to replace the door with the agreement that you pay him $2,000. By replacing the door, the contractor gives you something of his own: his skilled labor. It’s up to you to make things equal again by compensating him for his work. If you don’t come through with the payment, you fail to relate to him properly. Yet because a human being is a social animal, you cannot flourish as a human being if you do not relate to other human beings and the broader society correctly. Paying him isn’t just about what he is owed; it’s also about who you are in relation to others.

When we consider religion as a virtue, we categorize it as a potential part of justice. Religion is a potential part of justice because, while it is similar to justice in most respects, it’s missing something. Through justice one renders to another what is due to him to establish equality. Through religion you render a debt to God for creating you, but you cannot reestablish equality like you did with the person who replaced your door. Nothing you give to God can equal what he has given to you.

Instead, it is sufficient to do what you can. Interiorly, you express religion through devotion and prayer. Devotion—the heart of religion—is the will to give yourself readily to what pertains to the service of God. Through prayer, you express your dependence on God by asking from him what you need.

We also express our devotion and prayers exteriorly through the exterior acts of religion. Not only are exterior acts signs for what is in the heart, but they also excite our hearts so that our devotion is more fervent (ST II-II, q. 81, a.7). One important exterior act is sacrifice. An exterior sacrifice expresses the interior sacrifice of the heart (Ps 51:18-19) where we hand over our souls to God and acknowledge him as our ultimate source of life and happiness (ST, II-II, q. 85, a. 2, corp.). God himself has taught us how to worship him properly and has provided for us through Christ’s sacrificial offering on the cross, which we offer to God through the Mass. He has positively commanded us to worship him in this way.

With all of that being said, religion is part and parcel of an integral human life, and without it that life would become shallow. Worship—both interior and exterior—is necessary for us to express our subordination to and dependence on God in everything. We need it to relate to God properly. It is necessary for us to do this through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, that supreme form of worship God has provided for us. It is necessary for us to observe the Lord’s Day, in keeping with Divine Law, to remind us that our final rest is in God. The bishops relaxed part of the Church’s discipline that regulates how these were observed for a time on account of a public emergency, but they never pretended to do away with our inextricable need for public worship.

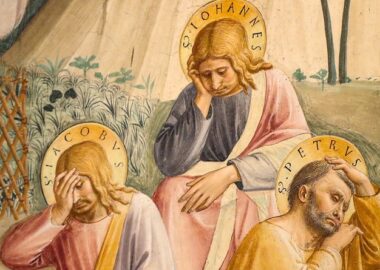

Image: Photo by Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

Originally posted on Dominicana Journal

The Dominican House of Studies

Forming Preachers of Truth in Charity.

Catholic theology in the Thomistic tradition for Dominican students and all who are interested in serving the Church, evangelizing the world, and growing in virtue, wisdom, and holiness.

Give